Resistance, 2016

RYAN! Feddersen: Resistance was the first in a series of solo exhibitions at the Missoula Art Museum that invite indigenous artists to make and show work at the museum through the generous support of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Meditations on Resistance

An introduction written by Gail Trembley

RYAN! Feddersen (b. 1984) is a gifted conceptual artist who creates thought provoking interactive works of art. She is showing four of her multilayered art installations as part of her exhibit, Resistance, at the Missoula Art Museum this winter. An enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, she is a descendant of the Okanagon and Arrow Lakes peoples, two of the twelve Indigenous nations from the Basin-Plateau region of Northeastern Washington that were located within the Colville Reservation boundaries. RYAN! grew up in Wenatchee, Washington South of the Reservation in a multi-cultural family where she learned about the stories, rich history and traditions that are part of her cultural heritage. Her work is influenced by her desire to celebrate what it means to be part of a contemporary American culture that has ancient stories and complex ties to the natural world. Feddersen is sensitive to things that the people who colonized and settled what is now called the United States seldom think about. RYAN!’s art works, like the legends about the famous Basin Plateau region culture hero, Coyote, often display the sensibilities of a trickster spirit that can make us laugh and think deeply about the human condition at the same time. Feddersen has created a unique art practice that often involves getting people who visit her exhibits to actively participate in the process of creating the art works she makes while they reflect on what that work means. After earning her Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree from the Cornish College of the Art in Seattle where she graduated Magna Cum Laude, RYAN! began to exhibit works at museums, art festivals and galleries in Washington, California and Montana. Her art practice is steadily gaining greater attention each time she shows her work.

Her current exhibit at MAM consists of two interactive installations and two that explore practices that inform us about the direction things are taking in the urban environment. The first work she chose for this exhibit, “Unveiling the Romantic West,” explores images of the Lewis and Clark expedition from two cultural perspectives, and is drawn in layers, the top one using thermochromatic ink which becomes transparent when touched. Viewers are directed to touch this work to reveal the layer below the surface and reflect on the differences in vision shown in the hidden layer. The top layer of drawings is based on the Missoula Courthouse Murals of the artist, Edgar S Paxson. While Paxson’s work is recognized as being more historically accurate than most other 19th Century Western painters; none-the-less, these paintings are full of factual inaccuracies, some in small details (for example. Meriwether Lewis’s dog was a Newfoundland, not the breed Paxson pictured, and the artist would have realized that if he had read Lewis’s Journals more carefully and studied the breed of the dog,) but more seriously it is narrow in its perspective. As a citizen educated to be part of a colonizing government that was still actively working to take Indian land and resources to enrich itself, Edgar Paxson promoted a simplified view of the narrative of exploration and settlement and idealized the colonial enterprise. Feddersen notes that Paxson’s works, “… reinforce the primacy of one narrative and decentralizes and obscures others.” She argues that Paxson’s paintings framed “… historical events through the lens of the dominant culture.” By creating drawings under Paxson’s images that contain the camas and bitterroot fields that fed the peoples who the explorers met and by picturing the tools Indigenous people used to harvest them as well as native animals like ground hogs, fish and eagles that filled the landscape, Feddersen presents a different perspective of what it meant to inhabit the Native landbase during the period of the expedition. By drawing the people’s clothing accurately, by decorating it with the indigenous designs used in the period and placing Indigenous people in the rich environment that sustained them, RYAN! Feddersen allows viewers who touch her work of art to use their own body heat to reveal information about native life during the period of Lewis and Clark not revealed in Paxson’s images. Her choice of thermochromatic ink also allows them over time to obliterate images that maintain the myths of the dominant discourse. In this way her art practice becomes a metaphor that leads viewers to a new way to appreciate history through their interaction with her work of art. This work is an elegant visual intervention that complicates viewers understanding of history.

Feddersen’s second work, “Disconnected Towers,” explores the effects caused by the rapid demolition and rebuilding of neighborhoods. When she moved to Seattle, RYAN! Feddersen lived in an extremely diverse neighborhood where people from different cultures, ethnic groups and races lived and intermarried. Indeed it was one of the most diverse neighborhoods in Washington state. She began to notice that contractors were building eight foot towers out of 4x4s and scrap 2x4s next to several houses close to her own, so they could attach the electrical wiring before they demolished these older houses in order to gentrify the neighborhood. For her the series of makeshift towers that make up her installation are beacons of impending change as developers build expensive houses and mansions that the former residents could not afford. This resulted in the slow, but steady transformation of the neighborhood as the ambition and greed of developers caused “…uncertainty,… exclusivity, and inequity” in the neighborhood. To the several wooden towers with their wiring, Feddersen adds a backdrop of images of buffalo skulls made of a fluoro acrylic plastic material that has a ghostly glow. This singular towering pile makes reference to the rapid extermination of the buffalo herds by settlers who wished to starve people in hundreds of Native American nations, so those settlers could take over the land and resources in the American west. This art installation becomes a poetic simile that connects the historic and modern forces that transform the relationships of people to the places where they live and love. It is an Indigenous reflection on what it means to remove populations so that people can profit from land and resources in both 19th and 21st Century America.

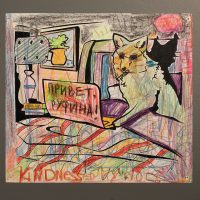

RYAN! Feddersen’s third work is, in her own words, “… a large scale collaborative drawing and coloring installation, “Coyote Now!” [that] takes the form of storyboards or vignettes. Made up of panels posted on the museum wall, it contains drawings that explore the contemporary adventures of Coyote. Ryan melted different colored crayons and cast them in the shape of Coyote bones. In traditional Okanagan tales, Coyote dies at the end of each story. These bone shaped crayons make reference to Coyote’s ability to die and be reborn if any scrap of bone, or fur remains after his death. Coyote is made immortal by the work of his cousin Fox who gained the power to resurrect him in Sweatlodge. At the beginning of each Coyote story, Fox brings him to life again. Feddersen created her Coyote bones so that they would symbolically become the fragments of Coyote’s remains needed to bring him back to life and make new tales possible. In order to complete this artwork, which pictures Coyote taking a the 21st Century camping trip to escape “…his busy modern life…,” viewers are instructed to use the crayon bones to color the images in Feddersen’s lively narrative. As this happens, the images come to life. In the powerful artist statement about this piece on her website, Feddersen writes, “The reference to the vehicle of Coyote’s immortality serves as a reminder that we can make the choice to continue the authorship of cultural practice, to be active in creating and reinforcing cultural identity while embracing indigenous methodologies. Essentially through our creative labors, we wield the power to bring coyote back to life.” This is an obvious invitation to viewers of her exhibit to get involved in supporting that endeavor while reflecting on the role of Coyote in the modern world. RYAN! Feddersen was inspired by the first English book of Coyote Stories by Okanagon writer, Christal Quintasket (b.1888) who published her work in 1933 under the name of Mourning Dove (the translation her publisher chose for her Indian name Hum-ishu-Ma.) In sharing these stories with the widest possible audience, Feddersen, like Mourning Dove, keeps the lessons taught by her ancestors alive for future generations and spreads the knowledge of them to a ever widening world.

The final artwork that Feddersen shows in this exhibit is called “Martha Stewart Cocktails.” This piece uses glass bottles and colorful felt to create a series of exploding Molotov cocktails, an object, which given its history, implies violence and armed rebellion. Invented by Republican fighters and used to attempt to destroy the Nationalist tanks during the Spanish Civil War against the Fascists under General Franco, the name for this weapon was coined by the Finns during World War II while they were being bombed and invaded by the Soviet Union. It is a reference to Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslay Molotov who signed a pact with Nazi Germany in late August of 1939 in hopes to discourage Hitler from invading the Soviet Union. In the end, it did not prevent that invasion, and so the Soviets themselves allied with the British and the Americans to defeat the Nazis. The Finns used Molotov Cocktails to attack Soviet Tanks, and during World War II various powers including Great Britian and the French Resistance fighters used these cheap, easily-to-produce weapons against the Nazis. Most recently they were used in the U.S. during the riots in Ferguson. Missouri after an unarmed African-American teenager, Michael Brown, was shot by a local policemen. It is interesting that Feddersen chooses to create multiple fiery looking sculptures by placing soft, dyed sheep fur in brittle glass bottles. There is both irony and humor in this body of work that uses Martha Stewart inspired “… principles of ‘the handmade, the homemade, the artful, the innovative, the practical, and the beautiful….’ ‘ to subvert the violence that these objects imply. These works seem to say even in a world full of injustice, it is time to use what are “…stereotypically feminine…” strategies to disarm the violence in our world.

In this exhibit, RYAN! Feddersen uses a wide variety of materials to create an art practice that inspires her viewers to get involved in her creative process. It also encourages them to think deeply about issues of culture and the way it defines our sense of both history and modernity in 21st Century America. Her work is rich in both humor and grace.

Exhibited:

2016-17 RYAN! Feddersen, Resistance, Missoula Art Museum, Missoula, MT.

This exhibition was created with the support of the Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Artist Trust and the Native Creative Project Development Grant through the Evergreen Longhouse.